PhotoVoice: Creativity, Community, and Co-Creation

From Wellbeing Sessions to Participatory Photography

The Positive Steps group became an important part of my practice—the people, the sessions were vibrant, and the energy in the room was always contagious. Around this time, I was becoming increasingly interested in participatory photography and had recently undertaken Photovoice training. A participatory research method that empowers individuals to capture their experiences and perspectives through photography, using images to spark discussion, reflect on social issues, and drive meaningful change.

Photography, for me, has always carried an ethical tension—between subject and object, between observation and agency. Candid street photography makes me wince; I never want to 'steal' someone’s soul. I was searching for ways to make photography a more collaborative and empowering process rather than an extractive one.

Creating the Photography Club

As I spent more time at the community centre, talking about my work and listening to the group, one of the members asked if I would run a regular photography club, the rest of the group were enthusiastic too. That’s when I had one of my signature thoughts: Why not bring two things together? I could test out participatory photography methods, and they could have their own photography club.

With this idea in mind, I secured a £5,000 neighbourhood grant, and we also gained an agreement to exhibit at the Whitworth Art Gallery—a major milestone for the project.

The Power of Intentional Photography

Working with the group on photography has been one of the most fulfilling experiences of my career. There is something profoundly moving about witnessing the moment when someone transitions from simply taking snapshots to creating intentional, expressive artwork.

It’s not just about photography; it’s about storytelling, identity, and power. The act of seeing, capturing, and sharing images became a way for to express their experiences, celebrate their heritage, and document their lives in ways that felt true to them.

While working as a freelance photographer at the University of Manchester, I had the opportunity to document some of the university’s community partners as part of their social responsibility work. It was during this time that I met the incredible Mo Blue—a force of nature, a community leader in Brunswick, and a champion of positivity.

Mo, innately talented at collecting people, after a brief chat about my work, immediately invited me to offer wellbeing sessions (for free!) for her Positive Steps group. I accepted, and what followed was a deep and lasting engagement with a community that welcomed me with open arms.

Exploring Visual Literacy

One of the things I love about photography and teaching visual literacy is that there’s a style, a story, or a subject for everyone. Exploring this with the group was such a joy. The participants—women over 55, from working-class Irish and African Caribbean backgrounds—brought such a depth of experience and perspective, shaped by the character of the area itself.

As we looked at different photographers, we were particularly struck by the work of Clarissa Sligh. Her piece Her Mother’s Hats resonated deeply with the group. Sligh’s reflections on her friend Delores, who was deciding what to do with the beautifully crafted hats her mother had left behind, opened up a conversation about generational shifts in formality. The group reminisced about the clothing their mothers and grandmothers wore to church—how these choices were not just about fashion but about dignity, pride, and community. It was a moment of shared recognition, of seeing how cultural identity is carried through objects and rituals, even as times change.

Later, I introduced the work of Nick Hedges, who had documented Manchester and Salford’s housing conditions in the 1960s for the charity Shelter. I wasn’t sure how the group would respond—these were not distant historical images, but ones that could reflect their own lived experiences or those of their families. I was aware of the ethical tensions around documentary photography, especially when it depicts poverty, and I considered the possibility that the images might feel intrusive, reinforcing a ‘poverty zoo’ dynamic rather than fostering agency. But the group engaged with them in a way that was both personal and political.

Rather than seeing themselves or their communities as simply the subjects of someone else’s lens, they recognised what Hedges was doing—capturing the structural inequalities that shaped their lives and the inadequate housing provision that so many immigrant families had to endure. There was a visceral anger in the discussion, not just about the past but about the ongoing impact of those policies and attitudes. What began as a conversation about photographs soon became a deeper reflection on social housing experiments, racism, and the way different communities navigated these challenges over time.

I left that session feeling energised. This was a Manchester I didn’t fully know—one that existed beyond my own experience but was being generously shared with me through these stories. And it felt like the start of something—perhaps a project, or perhaps just a space for more of these conversations to unfold.

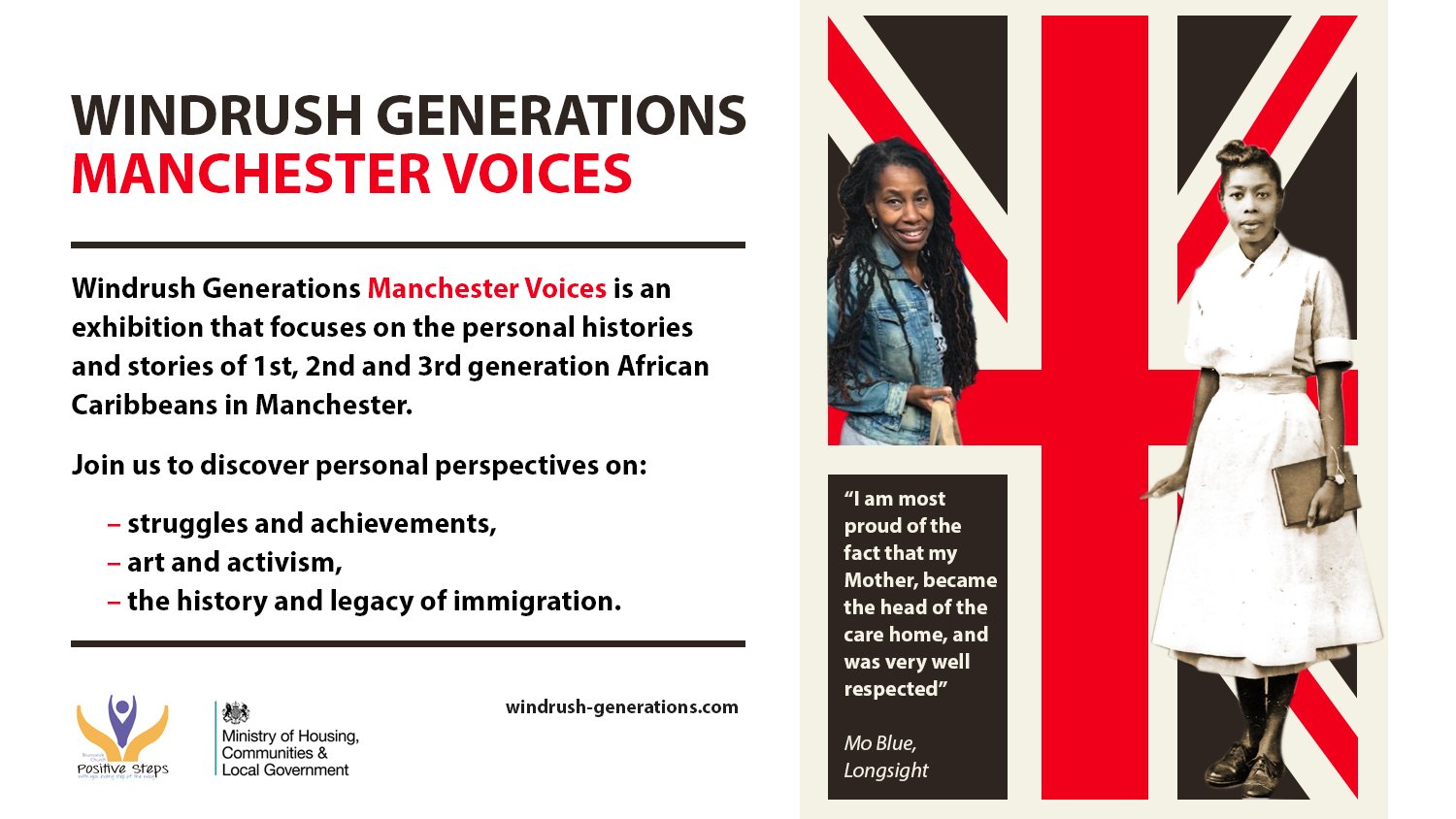

Manchester’s Voices: Windrush Generations

When the group spoke back to the images—naming the injustices they lived through—it became clear that their own stories needed to be seen, heard, and valued. That moment lit the fuse for what became the Windrush project.

In 2018, I partnered with the community group Positive Steps, local Black organisations, schools, and Manchester Central Library to secure funding from the government’s Windrush Fund. The aim was simple but vital: to honour the contributions of the Windrush Generation, strengthen community belonging, and educate the wider public about their experiences.

As the creative facilitator and project manager, I took on multiple roles.

I secured funding and managed stakeholder engagement, ensuring that community voices shaped the project from the start. This wasn’t about delivering a top-down initiative—it was about collaboration, making sure the work reflected the people it was for.

I planned and implemented a series of events, workshops, creative sessions, and a public exhibition. The project wasn’t just about history—it was about connection, creativity, and recognition.

I managed the budget and reporting, keeping everything on track while demonstrating accountability to funders.

Most importantly, we saw real impact. The Manchester Central Library exhibition attracted over 5,000 visitors. Our Facebook campaign reached 1,800 people. Participants reported an increased sense of well-being and belonging. The project didn’t just document history—it created a space where people felt seen and valued.

But then, just as we found out we had secured the funding, the pandemic hit.

For most, the instinct was to postpone. I later learned that many projects went on hold. That never crossed my mind. If anything, the lockdown made the project more urgent. Recognizing and celebrating Windrush pioneers wasn’t just politically important—it was personal. I had deep relationships in this community, and I knew the power of storytelling. I also needed to keep going—I had to work.

So, we pivoted.

We moved everything online. I sourced tablets for participants and created an online writing group. Teaching digital photography in person had already been an accessibility challenge—now I had to coach tablet use over the phone. It became an exercise in patience, creativity, and trust. Slowly, step by step, we figured it out together.

Looking back, those moments stand out. Not just the finished project, but the process—figuring out new ways to connect, to enable, to keep people involved when the world felt like it was closing in. The project was always about voice and visibility. In the end, it became something even deeper: a testament to resilience, creativity, and the power of community, even in isolation.

One of the most powerful aspects of this project was creating space for interpretation—inviting people to engage with the brief in their own way, to find creative expression in whatever form felt most natural to them. Some took photos, some wrote reflections, some experimented with entirely new ways of telling their stories.

Julie, a poet, wanted to contribute through spoken word. Her poem became part of the project, not just as an individual act of creativity, but as a reminder of what storytelling can be—fluid, personal, and deeply meaningful.

This is at the core of digital storytelling: you don’t need access to professional production tools. The power of a story isn’t in how polished it looks, but in the choice to share it. In making that choice, people assert their voice, their presence, and their place in history.